REMEMBERING THE NEWSROOM: THE GAZETTE, MONTREAL, 1957-59

Home page | Royalty opens St. Lawrence Seaway

Working the police beat: fires and crimes

PICTURES AND STORIES about the fire dominated the front page, as it was torn apart and re-designed between editions. Developments continued through the night and into the early morning hours, resulting in this rare "extra" edition.

Checking on a downtown fire alarm leads to first big story

I had been at The Gazette for less than three months when I stumbled into my first big story. There had been a fire alarm at the Windsor Hotel, then one of Montreal's most expensive and most famous hotels, home-away-from home for visiting royalty. It was at the corner of Peel St. and Dorchester Blvd.(now Rene Levesque Blvd.), not far from the newspaper building, so the city editor told me to go out and have a look. It was a cold December night in 1957, almost 11 o'clock. The paper's first edition had already been printed, and the next one was about ready to go.When I got to the hotel, there were some flames and smoke coming out of upstairs windows, so I alerted the city desk from a nearby payphone that yes, the hotel was indeed on fire. I did some interviews, then went back to the office to write as Gazette photographers and other reporters arrived on the scene.

'Buffaloes' did public relations for fire department

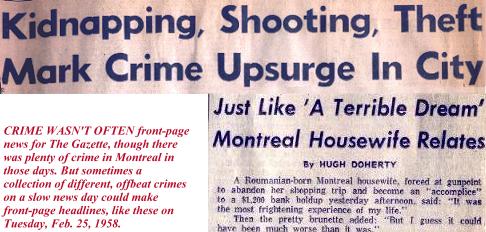

The Gazette didn't often give much space to murders and robberies, unless they were unusual, but it gave lavish coverage to fires, which were part of the police beat. So police beat reporters like me developed a close relationship with the Montreal Fire Department, which, in turn, was very public relations-conscious.

Attached to the department was a group of men called "buffaloes." They were mostly retired firemen, and one of their assignments was to phone all the city's police reporters and photographers whenever a major fire broke out at any time of the day or night. The "buffaloes" had home phone numbers as well as office numbers. It was part of my job to have a phone at home beside my bed to receive their calls during off-hours and to rush to the fire scene. I covered so many fires most of my working clothes smelled of acrid smoke.

THE GOLDEN HELMET AWARD for best fire coverage in the city was started by the Montreal fire department in 1959. Its first winners in October of that year were members of this Gazette team. From left, Al Palmer, reporter; Walter Edwards, photographer; Gordon Pritchard, photographer; Armand Durette, chief of the Montreal fire department; Brian Cahill, reporter; Hugh Doherty, reporter. Cahill was actually the paper's medical reporter, but had been pressed into service one night during a particulary serious fire when the reporter assigned originally to cover the blaze retired instead to a nearby tavern and became very drunk very quickly. (Gazette Photo Service)

Newsroom desk plugged into city's police and fire calls

The regular police beat consisted of three people. Two junior reporters manned the police desk in the newsroom, one during the day and one at night until 2 a.m. A senior police reporter was based at the press room at Montreal police headquarters near city hall.The police desk was located beside the city desk and was equipped with police radios and fire alarms that were extensions of the departments' systems. The newsroom radios were always on.

Hourly checks by telephone with all the city's police stations

Reporters on the desk shifts had to learn and listen to all the police and fire call codes. They had to check by telephone with each of the city's 20 or so police stations every hour. And they phoned area municipal fire and police stations, and Quebec Provincial Police headquarters periodically. They kept the city desk and the senior police reporter downtown up-to-date on whatever news they gleaned.

The senior reporter generally covered major crime or fire stories, but often the desk reporter and he collaborated, and if the story was big enough, other beat and general reporters became part of the coverage team.

Training on the job with a skinny, energetic veteran

When I first started on the police desk, the senior police reporter was Vince Rowe. He was a small, skinny guy with a big nose, large glasses and a narrow, balding head; an energetic veteran journalist who could do any job in the newroom, from desk work to reporting and even editing the church pages.He played a mean card game of hearts, too, which was the main activity around the city and news desks when things were quiet late at night after the first edition of the paper had been printed. Vince was a reformed alcoholic, so he wasn't one of the press club crowd.

Vince trained me in the mechanics of the police desk, and then showed me around Montreal police headquarters, teaching me the mysteries of the police beat. The senior police reporters for all the newspapers hung out in a press room adjacent to the offices of the police detectives. The La Presse man was Roger Champoux and for The Montreal Star, it was Larry Conroy, veterans both.

After a while, I got to fill-in for Vince on his days off and holidays as The Gazette's senior police reporter.

Teaming up with out-of-work former nightlife columnist

But it wasn't long before Vince was off the police beat and back as an editor on the news desk. He was replaced on the beat by one of Montreal's most celebrated and colorful journalists, Al Palmer. Ever since the Montreal Herald had folded on October 18, 1957 after 146 years of publication, Al had been without a job. So The Gazette had decided to hire him as its senior police reporter. At the Herald, he had for years written a very popular column called "Cabaret Circuit;" all about Montreal's teeming nightlife and its seamy underworld. Al had also written two books about Montreal, one of them a novel. His particular brand of journalese was irreverent and full of slang. Now, as a Gazette reporter and not a columnist, he would have to write in the paper's conventional, straightforward news style.

At the Herald, he had for years written a very popular column called "Cabaret Circuit;" all about Montreal's teeming nightlife and its seamy underworld. Al had also written two books about Montreal, one of them a novel. His particular brand of journalese was irreverent and full of slang. Now, as a Gazette reporter and not a columnist, he would have to write in the paper's conventional, straightforward news style.

As the junior police desk reporter who would be working the most with Al, I was at first quite a bit in awe of him. But I needn't have been. I found him to be a quiet, soft-spoken, friendly man, who talked often about his wife and daughter. He was tall and handsome, with thick, wavy silver hair that was always well-coiffed. He wore expensive, well-tailored suits, white monogrammed silk shirts with cuffs and silver monogrammed cufflinks. He always wore a conservative tie, and his shoes were always clean and shiny. His favorite colour for suits and ties was light or dark gray.

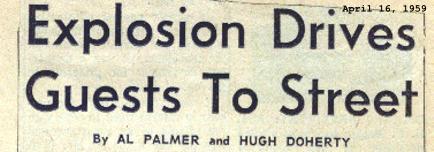

As with Vince, I filled in for Al as senior police reporter on his days off and holidays. And over the next year or so, we teamed up on many crime, disaster and fire stories, often sharing bylines, like the one below:

THIS SHARED BYLINE was for coverage of an explosion in the Queen's Hotel, just around the corner from The Gazette. A man in one of the rooms had killed himself with 20 sticks of dynamite. Two other people were injured, and the hotel was extensively damaged. Coverage had to be quick; the explosion occurred not long before deadline for the first edition.

Al had been justly famed at the Herald for his contacts in both the city's underworld and its various police forces, and he brought those contacts with him to The Gazette. If, for example, I heard code calls on the police radio for some kind of raid, I would phone Al at police headquarters about it. He would check around and phone back. Often, he said, "they're not going to find anything, so there won't be a story." That was Al working his underworld sources. I once asked him how he mantained all his contacts, and he said the secret was trust. He said he never let the cops know what the crooks were doing, and vice-versa.

One of the more unusual drinking spots he introduced me to was the St. Gabriel tavern, in the old part of Montreal. It turned out the tavern was a favorite hangout for members of the Quebec Provincial Police, an organization noted then for its secrecy and high-handed enforcement methods. Journalists sometimes called it "Duplessis' Gestapo," a reference to the often-dictatorial tactics of Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis. For Al, the St. Gabriel was a great place to polish and maintain his QPP contacts.

Scooping the competition on the roof of a broadcasting building

One of Al's biggest scoops at the Herald had come in 1946 when a gangster named Louis Bercovitch shot and killed Harry Davis, one of Montreal's most notorious gambling czars. Bercovitch had surrendered not to the police, but to the Herald and Al, claiming delf-defence. Now, in the mid-1950s, Bercovitch had served his sentence and was being released. All the newspapers, radio stations and TV stations wanted to interview him, but Al and The Gazette got the story first. Al talked to Bercovitch in secrecy, outdoors, up on the roof of the old Canadian Broadcasting Corporation building on Dorchester Blvd.Al had all kinds of other city contacts besides those in the underworld and police departments. One night, he and I teamed up to cover the suspicious death of a man downtown. For some reason, police would not tell anyone, not even Al, how the man had died, or whether foul play was involved.

So Al took me to the Montreal morgue, then located in a very old stone building in Old Montreal, around the corner from Notre Dame Cathedral. It was on a dimly lit, narrow street -- a creepy, eerie place. Al greeted the elderly attendant there by name, and asked if we would see the body. "Sure," was the answer, "come with me." Well, I didn't really want to look at a dead body on a morgue slab, so Al went alone with the attendant. When he came back, he told me the body had a bullet hole in it. Armed with this information, we went back to the police and came up with a murder story.

It ended up as a few paragraphs buried deep inside next morning's Gazette.

Back to home page | Royalty opens St. Lawrence Seaway

Comments? Click here to E-mail

This page was started June 18, 2002. Last updated April. 9, 2006