REMEMBERING THE NEWSROOM: MONTREAL 1957-59

Working the police beat | Royalty opens St. Lawrence Seaway

THE GAZETTE NEIGHBOURHOOD, winter of 1957. The Gazette building is the big one in the background with the old Canadian Red Ensign flying from a pole on the roof. Built in the late 1920s, it was situated at 1000 St. Antoine Street, on the corner of St. Antoine and Cathedral Streets, and was the Gazette's home until 1980. The newsroom was on the fourth floor. I took this picture looking south down Cathedral Street, standing near the southeast corner of Dominion Square.

Bottles of gin to keep pace with the city

When I first went to work as a night police reporter for The Gazette in the fall of 1957, it was often one of my duties to walk over to the Mountain Street liquor commission store, which was always open late, and fetch a 26-ounce bottle of Vicker's dry gin for one of the desk men. It was his second of the evening; he started his shift with the first. And he would finish the second before quitting time.

It was that kind of paper, and that kind of city. Not that everyone on the news staff boozed through each shift. In fact, most didn't. But a lot of drinking did go on, not only in the newsroom, but all over town. Montreal in the 1950s was an exciting, wide-open city of sin, as it had been for quite a few years. There were bars and strip joints everywhere downtown, and they all seemed to stay open into the wee hours and even all night. Civic reformer Jean Drapeau had tried to clean things up in the mid-1950s, first with an inquiry into corruption in the city's police force, and later, by getting himself elected mayor, but he ran out of steam for awhile in the fall of 1957. He lost that election, and was replaced as mayor by Sarto Fournier, so Montreal continued on it's merry and raffish way for a few more years.

Montreal in the 1950s was an exciting, wide-open city of sin, as it had been for quite a few years. There were bars and strip joints everywhere downtown, and they all seemed to stay open into the wee hours and even all night. Civic reformer Jean Drapeau had tried to clean things up in the mid-1950s, first with an inquiry into corruption in the city's police force, and later, by getting himself elected mayor, but he ran out of steam for awhile in the fall of 1957. He lost that election, and was replaced as mayor by Sarto Fournier, so Montreal continued on it's merry and raffish way for a few more years.

That's when I was hired on as a 23-year-old junior reporter, manning the police desk in the newsroom from 6 p.m. to 2 a.m., which were the busiest hours for a morning newspaper like The Gazette. Accidents, fires, robberies and murders were my main professional concern for the first few months. There were a lot of them all in Montreal then. Later, as I acquired a bit of seniority and big city experience, I became a general reporter and covered a variety of stories. I had already put in four years, off and on, working at the Sherbrooke Daily Record before moving up the The Gazette, so I seemed to fit in fairly quickly. I'm sure it helped that my grandfather, George MacDonald, had been day editor of The Gazette from 1947 until his death in 1955.

I joined reporters and deskmen at some of their favorite drinking spots. Supper on the night shift was often a "birdbath" or two (or more) at Mother Martin's, at the corner of Peel and St. Antoine. A "birdbath" was a double martini served in an outsize martini glass. Sometimes, we went across the street from The Gazette to the Prince Tavern for tabletops-ful of draft beer and cheap but delicious tavern steaks. After work, there was always the Montreal Men's Press Club in the Mount Royal Hotel, where one could drink "on the tab" for several weeks before being presented with a bill. Those that couldn't ante up were banned from the club until their account was cleared. And there were any number of downtown bars and lounges that only started to come to life after 2 a.m.

ELECTRIC STREETCARS downtown, February 1956. These were Montreal's main public transportation in the days before subways and the widespread use of diesel buses. Trams were in use in some parts of the city until 1959.

Streetcar tickets and moonlighting to make ends meet

As on most Canadian newspapers then, there was no newsroom union, no overtime, no pension plan, no company cars for city journalists. Gazette reporters usually travelled to and from assignments in photographers' cars when a photographer was assigned. Otherwise, they went by streetcar and bus, using tickets carefully doled out two at a time by the city desk. When time was short, and the story fairly important, taxis could be used, using "chits" from the same source.Salaries were generally not very handsome; my starting wage was $75 a week. So a lot of "moonlighting" of various kinds went on to make ends meet. Some of the reporters were invited to write editorials on the side. Eventually, I became one of them, and was paid $5 for each published editorial. I also wrote editorials for my old paper, the Record, and mailed them in. They netted $2 per piece. One of the deskmen introduced me to a city weekly "scandal sheet" called Midnight owned by Joe Azaria. The deskman was an editor at Midnight on his days off, and he showed me to how make some off-hours money simply by re-writing court stories already published in the The Gazette. No facts were changed or omitted; the trick was to re-write each story in much more racier language than had originally been used. Midnight ran a lot of these, and they were worth $10 each to the re-writer.

Incentives to earn extra cash were sometimes very strong. My editorials and Midnight work went a long way towards paying hospital and doctors' bills for the birth of our first-born in the days before Canadian medicare.

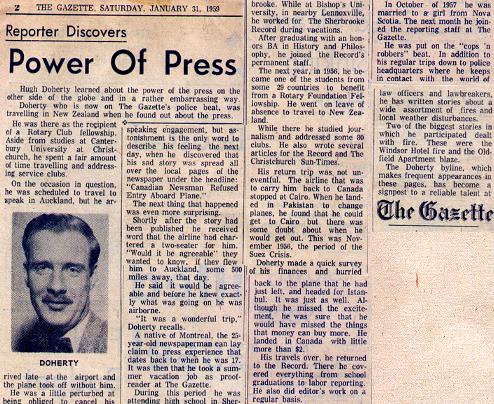

PERHAPS TO TRY AND COMPENSATE for small salaries, in 1959 the paper ran a series of laudatory articles about its own reporters and other editorial staff. Here's the story someone (I forget who) wrote about me.

A "reporters' newspaper" but timid with the premier

There was only one other Montreal English-language daily then -- the afternoon Montreal Star (it shut down in 1979). It was much bigger than The Gazette, both in bulk and circulation. A third English-language daily, the Herald, was closed down in October, 1957, a month before I joined The Gazette. The Herald was a racey noon-hour tabloid that had been in existence since 1811. Both the Star and The Gazette inherited some of the Herald's photographers, reporters, columnists and sports writers, but none of the taboid's flare and cheekiness. The main French-language daily was La Presse, the largest in Quebec. Next largest was Montreal-Matin. The city's other French-language daily newspaper was Le Devoir, much smaller than either of the other two but regarded then, as it is still, as an independent, influential journal.The Gazette was known within the Montreal newspaper world as a "reporters' newspaper," which meant reporters were expected to find a lot of their own stories, and to write them well enough that they didn't need to be tampered with by copy editors. As a result, reporters for the much larger Star often seemed to suffer from an inferiority complex, and had to endure being told by their editors to "match" stories by Gazette reporters. That's why, when reporters from both papers found themselves on the same assignment, the Star reporters invariably tried to find out what the Gazette reporters were going to write about.

Not that The Gazette was a particularly courageous,

crusading kind of newspaper. In fact, when it came to provincial politics, it was downright timid. This was the heyday of Maurice Duplessis, dictatorial premier for some years of Quebec at the head of his own Union Nationale party. And both The Gazette and the Star supported him slavishly, not only in their editorials, but often in their news columns as well. In the late 1950s, when Le Devoir broke news about Duplessis cabinet ministers getting rich through illegal insider trading of Quebec Natural Gas shares, Gazette reporters were ordered not to do any independent reporting of the story. All they were allowed to do was repeat what Le Devoir printed, using only that paper as the source. This went on for some weeks, and was the cause of some angry shouting matches in The Gazette newsroom between frustrated senior reporters and the editors who muzzled them.

And both The Gazette and the Star supported him slavishly, not only in their editorials, but often in their news columns as well. In the late 1950s, when Le Devoir broke news about Duplessis cabinet ministers getting rich through illegal insider trading of Quebec Natural Gas shares, Gazette reporters were ordered not to do any independent reporting of the story. All they were allowed to do was repeat what Le Devoir printed, using only that paper as the source. This went on for some weeks, and was the cause of some angry shouting matches in The Gazette newsroom between frustrated senior reporters and the editors who muzzled them.

When it came to Duplessis, both The Gazette and the Star officially took the view that because they represented the English-speaking minority in Quebec, it was not their place to be overly critical of a provincial government that represented the French-language majority. Unofficially, the word was that Duplessis threatened to put a heavy tax on the newsprint supply of any paper that displeased him. In any case, the readers of The Gazette and Star didn't agree with their newspapers. In provincial elections, English-speaking Montrealers always voted heavily against the ruling Union Nationale.

The company proprietor who wouldn't depart quietly

The president of the Gazette Printing Company, which owned The Gazette, was John Bassett, Senior, a native of Ireland and

long-time famed Canadian journalist and newspaper proprietor. He died at the age of 72 in 1958, and of course, his newspaper gave his life and times full, detailed coverage. But over in the section of the paper devoted to notices of births and deaths, there was hell to pay. Right at the very top of the "Births" column was the name "Bassett." It only lasted for one edition -- the appropriate adjustment was made for succeeding editions, but that was enough to launch a legend. There were fond chuckles throughout the newsroom. Bassett, it was said, could not resist reaching out from the grave to play this last practical joke.

The president of the Gazette Printing Company, which owned The Gazette, was John Bassett, Senior, a native of Ireland and

long-time famed Canadian journalist and newspaper proprietor. He died at the age of 72 in 1958, and of course, his newspaper gave his life and times full, detailed coverage. But over in the section of the paper devoted to notices of births and deaths, there was hell to pay. Right at the very top of the "Births" column was the name "Bassett." It only lasted for one edition -- the appropriate adjustment was made for succeeding editions, but that was enough to launch a legend. There were fond chuckles throughout the newsroom. Bassett, it was said, could not resist reaching out from the grave to play this last practical joke.

Presiding over the newsroom in those days was managing editor Harry J. Larkin, another Irishman; short and pudgy with wavey, greying hair, sharp features and cold (it seemed to me) blue eyes. He became, as they say, a legend in his own time, apparently serving as a journalistic model in not one but two novels that later became movies. One was Brian Moore's The Luck of Ginger Coffey, published in 1960 and in which he was transformed into a cantankerous Scot by the name of MacGregor. The other was William Weintraub's Why Rock the Boat?" published a year later, in which Larkin became Philip L. Butcher, "tyrannical and penny-pinching," in Weintraub's own words. Both authors had worked under Larkin as reporters at The Gazette.

Larkin had his own office, of course, and was not often seen in the newsroom itself. Once, in 1958 or 1959, he came out to distribute a memo that announced he had arranged for all editorial staff to receive polio vaccine. This caused a great stir because Montreal was in the midst of an unexpected summer polio epidemic; unexpected because Salk anti-polio vaccine had been developed some years before, and it had been thought this had resulted in the eradication of the often fatal illness. So now there was a severe shortage of the vaccine and the city was nearly in panic as the number of polio cases increased. Word went around the newsroom that the supply for The Gazette was somehow illicit; perhaps from a black market that had sprung up. As far as I know, there was ever any evidence that this rumour was true, but a number of us, including me, declined the vaccine offer anyway.

Paper's unique character came from it's editorial staff

The Gazette editorial staff included a number of "one-of-a-kind" specialists who helped give the paper it's unique character. The classical music and drama critic and columnist was scholarly Thomas Archer. The entertainment and nightclub critic was Harold Whitehead, a mountain of a man with a wild, walrus-style black moustache. Fitz was the pen name of Gerald FitzGerald who wrote a daily "about town" gossip column called "On and Off The Record." (To read one of his columns from 1959, click here.) And the editorial cartoonist was John Collins, one of North America's great newspaper cartoonists.

COLLINS CARTOON: This original never made it into any collections of Collins' cartoons. Collins drew it to go with a front page story I wrote about Groundhog Day, Feb. 2, 1959, and later, gave it to me.

The paper's publisher was Charles Peters, himself a former newsman. Edgar Andrew Collard was the editor but he had nothing to do with the news department. He wrote editorials, and was well-known for his historical articles and books.

The city editor was Walter Christopherson and he was my immediate boss. He also became my unofficial mentor, encouraging me and giving me a great deal of freedom in finding and writing stories. He was tall and thin, forever hitching up his trousers, slightly swarthy of complexion, with a fringe of greying dark hair around his balding head. He wore large, horn-rimmed glasses and seemed to me to be totally unflappable, even when the most chaotic news situations were whirling around him. That's Walter on the left, just as I remember him: phone cradled to one ear, taking notes furiously, paste-pot at the ready. Walter was also an accomplished classical pianist and once told me he had started out to be a concert performer. In his off-hours, he wrote a weekly review of classical recordings for the paper.

The city editor was Walter Christopherson and he was my immediate boss. He also became my unofficial mentor, encouraging me and giving me a great deal of freedom in finding and writing stories. He was tall and thin, forever hitching up his trousers, slightly swarthy of complexion, with a fringe of greying dark hair around his balding head. He wore large, horn-rimmed glasses and seemed to me to be totally unflappable, even when the most chaotic news situations were whirling around him. That's Walter on the left, just as I remember him: phone cradled to one ear, taking notes furiously, paste-pot at the ready. Walter was also an accomplished classical pianist and once told me he had started out to be a concert performer. In his off-hours, he wrote a weekly review of classical recordings for the paper.

His city desk assistants were Bruce Croll, Patrick Nagle and Clell Bryant. The news editor was Alan Randal, a former war correspondent for the Canadian Press. His assistant was Brodie Snyder. Two of the other deskmen were Bob Jamieson and Oliver Clausen. The day editor was Karl Gerhardt, a former German submariner. The sports department was led by Dink Carroll, Paddy Curran and Vern DeGeer. The business editor was John Meyer, the Ottawa bureau chief was Arthur Blakeley and the Quebec City bureau chief was Wilbur Arkison.

The Canadian Press staffer in our newsroom was George Frajkor.

If there was a star on the reporting staff, it was Bill Bantey, who didn't appear to have any fixed beat, but covered many of the major stories, no matter what the subject, and did a lot of investigative reporting. Some of the other reporters included Myer Negru (Montreal city hall); Tiger Gilliece (criminal courts), Leon Levinson (criminal and civil courts), Brian Cahill (medical), Lauchie Chisholm (air transport), Clayton Sinclair (marine), Bob Hayes (suburban politics), Martin Sullivan (general), Joe Emery (general), Jim Ferrabee (police desk), Vince Rowe (police, general, and news desk), Al Palmer (police), Noel Moore (general), Tom Telfer (general).

The Gazette Photo Service was run by photographer Gordon Pritchard, and the other photographers were: Walter Edwards, Bob James and Larry McInnis.

I don't recall a single woman in the newsroom when I was there; not in the sports department (which was part of the newsroom), not on either the city desk or news desk, not among the reporting staff. What was then known as the women's department was not part of the newsroom, but occupied separate quarters. I never did find out where.

So the newsroom itself was very much a kind of all-male club, noisey with the clatter of typewriters, the ringing of telephones, and the bilingual muttering of the police radio, smokey with the fumes of tobacco from the cigarettes almost everyone used, like a sweatbox in the humid Montreal summers (offices were not air conditioned in those days), untidy and paper-strewn, a-bustle with people and conversation as deadlines approached. Just like in the old movies.

(With thanks to Robin Frizzell of the Montreal area, Walter Christopherson's eldest daughter, who e-mailed me the picture of Walter on this page after running across the web site in September, 2005.)

MORE NEWSROOM MEMORIES

Working the police beat | Royalty opens St. Lawrence Seaway

Comments? Click here to E-mail

This page was started May 22, 2002. Last updated April. 9, 2006