The first newspapers on

Canada's west coast: 1858-1863

By Hugh Doherty: Copy editor, city editor, The Daily Colonist, Victoria, B.C., 1968-73. Based on a research paper done at the University of Victoria graduate history department in 1973.

Introduction

The first modern printing press on what is now Canada's west coast came

to the British colony of Vancouver Island on the mad tide that was the

Fraser River gold rush of 1858. It arrived in the tiny community of

Victoria from San Francisco, and so did hordes of American

prospectors, storekeepers, outcasts, land-sharks and other

opportunists.

Soon, the press was producing the young colony's first newspaper, and both press and newspaper must have been regarded as very mixed blessings indeed by Governor James Douglas, whose fear of American domination, even annexation, was never far from the surface. Douglas was governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island and also of the separate Mainland Colony of British Columbia. At the same time, he was chief factor for the Hudson's Bay Company, which tended to regard both colonies as private fiefdoms, and he ran them accordingly.

Like the first gold-seekers, Vancouver Island's first newspaper was a harbinger of others; a small host of them over the next five years, some determined to put the news pioneer out of business, some simply trying to emulate it for profit. Between 1858 and 1864, ten newspapers were started in Victoria, half of them dailies:

- Victoria Gazette #1 1858-1859

- Vancouver Island Gazette 1858

- News Letter for Vancouver Island and New Caledonia 1858

- Le Courier de la Nouvelle Caledonie 1858

- The British Colonist 1858-1980 (The Daily Colonist)

- New Westminster Times and Vancouver Island Guardian 1859-1861

- Victoria Gazette #2 1859-1860

- The Daily Press 1861-1862

- The Victoria Daily Chronicle 1862-1866

- The Daily Evening Express 1863-1865

- Cast of characters

By the end of the period, with Douglas preparing to leave public life, there were only three. In the interval, the gold rush changed the character of the colony and the direction of Douglas' life, spawning conflicts that were reflected among the newspapers as the early journalists jostled for their place, too, in a suddenly-new society.

Victoria Gazette #1

June 25, 1858 - Nov. 26, 1859The process of rapid change began in earnest when the steamboat Commodore docked in Victoria with the first big load of gold miners from San Francisco.

During that summer of 1858, a settlement of

about 500 became a community of well over 5,000 and business

boomed, most of it financed with San Franciscan capital. In mid-June,

hard on the heels of the miners, another ship from San Francisco

arrived. Off it came California newspapermen James W. Towne, Henry C. Williston and Columbus Bartlett

, and "a complete

printing office." The three put out a sample newspaper so that

advertising could be sold, and four days later, began regular bi-weekly

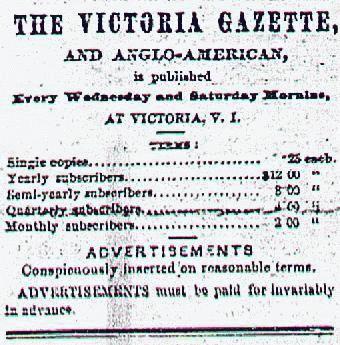

publication of the Victoria Gazette and Anglo-American.

During that summer of 1858, a settlement of

about 500 became a community of well over 5,000 and business

boomed, most of it financed with San Franciscan capital. In mid-June,

hard on the heels of the miners, another ship from San Francisco

arrived. Off it came California newspapermen James W. Towne, Henry C. Williston and Columbus Bartlett

, and "a complete

printing office." The three put out a sample newspaper so that

advertising could be sold, and four days later, began regular bi-weekly

publication of the Victoria Gazette and Anglo-American.

The Gazette emerged from a mushrooming of American

newspapers that started with the California gold rush of the 1840's

and spread north. After the first California newspaper was established

in Monterey in 1846, the scramble to print newspapers rivalled the

gold rush itself. By 1860, there were 100 newspapers in California,

40 of them in San Francisco. By 1848, there were newspapers in

Oregon City and Olympia in Oregon Territory.

The American newspapermen who came to Victoria had been

deeply involved in the California newspaper boom, and their new

journal was part of a loose chain of publications.

The first problem they encountered in their Victoria venture

concerned a name. They had originally intended to call the newspaper

the Anglo-American and a sample edition appeared under that name.

There do not appear to be any copies of this sheet still in existence. But there is no doubt it was published; probably the first material to be printed on Vancouver Island.

There do not appear to be any copies of this sheet still in existence. But there is no doubt it was published; probably the first material to be printed on Vancouver Island.

The first number of the regular issue appeared with the Gazette masthead on the front page, above (To see what the entire front page looked like, click on the masthead). But there was also a small box under the masthead (left) with the title Victoria Gazette and the words "and Anglo-American" underneath in small letters. A few issues later, all reference to anything American had disappeared. The proprietor had been persuaded to substitute Victoria Gazette for Anglo-American at the suggestion of "many citizens of Victoria."

The strongest suggestion may well have come from Douglas himself. Certainly, he took more than a casual interest in the fledgling newspaper, appearing with Hudson's Bay officials at the Gazette office within the fort walls to watch the first issue being printed and sending two copies of the product to Hudson's Bay headquarters in London.

The Gazette was a thoroughly professional undertaking from the

start. Small in size (similar to a modern tabloid), it was designed to be

folded and carried about easily; an important feature because the

Gazette was aimed at itinerant gold miners as well as town residents.

A Weekly Gazette was published, consisting of re-prints of the main

news carried during the previous week. A Steamer Gazette for reading

on voyages between Victoria and the mainland, or San Francisco,

collected news and editorials fortnightly for re-publication, with some

editions featuring a steel engraving of a Victoria scene. The Gazette

advertised for commercial printing work, and its shop was soon

turning out many kinds of printed material.

The development of job printing in conjunction with newspaper

publishing was to have important implications, both for the Gazette

and for other colonial newspapers, because the profitability of

newspapers often depended on income from other kinds of printing,

leaving the way open to government and other influences.

To attract readers, the Gazette cast its net widely; to Fort

Langley, Fort Hope and Fort Yale in gold-rush territory; to

Washington and Oregon territories, and back to California. A month

after its founding, the Gazette had brought a bigger press from San

Francisco, began daily publication (except Sundays and Mondays), and

devoted more than half of its space to advertising, about a third of

which was from San Francisco. In the absence of a government

gazette, space in the newspaper was purchased for proclamations,

notices and other official communications. Sometimes, these occupied

more than a page of the four-page Gazette.

Editorially, the Gazette at first avoided being either critical or controversial. It was not intended, the owners said in their first regular edition, "to make the Victoria Gazette the organ of opinion on any save the more practical questions of the moment..." Instead, it would concentrate on plain facts, particularly about the natural resources of the region. By "natural resources," it soon became clear that the Gazette meant gold almost exclusively. It sent reporters on extended trips to the gold fields of the Interior, first Columbus Bartlett and later John Damon, who wrote under the pseudonym of "Curioso." Sensitive to its position as an American enterprise in a British colony, the Gazette would occasionally arouse itself from innocuousness and spring fiercely upon any suggestion that it was opposed to the Douglas regime or represented American opinion. By the end of Volume 1, the Gazette found it necessary to repeat its statement of position. There would be no political agitation in Gazette columns because, in an area where the population was largely migratory and alien, such writing would be "premature and unwise." In any case, it would be improper for the Gazette proprietors, as Americans, to take the lead in political discussion involving the British government. Developments were soon to force the owners to deviate from this policy, to their sorrow.

Vancouver Island Gazette

July 28, 1858 - Sept. 1858 (?)Meanwhile, during the last half of 1858, four other newspapers were founded, eddying like the Gazette in the wake of the Fraser River gold rush. In July, Frederick Marriott, an Englishman from San Francisco, brought out the Vancouver Island Gazette, apparently hoping to make it an official government publication. In addition to local news, it did carry some government notices, but it never received official sanction, and sometime during the late summer or early fall, it ceased publication.

News Letter for Vancouver Island and New Caledonia

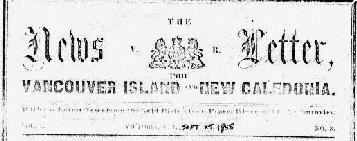

Sept. 1858 - ?Marriott made another attempt at Victoria publishing with the News Letter for Vancouver Island and New Caledonia, one of the more interesting curiosities of early Vancouver Island journalism.

Patterned after a gold-field journal Marriott had started in California, the News Letter was a four-page, letter-sized newspaper, printed on blue-lined paper that could be folded once and carried in one's pocket. The last page was left blank so that miners could use it for making notes or writing letters. Only one copy of the News Letter was known to exist in 1972, and it was signed "John Bull on the Pacific." Above is a photocopy of the masthead of that newspaper for Sept. 25, 1858, its third issue. (To see a full-size photocopy of the entire front page, click on the image.)

Le Courier de la Nouvelle Caledonie

Sept. 11, 1858 - Oct. 8, 1858 (?)Marriott was also involved in printing another oddity, the French- language Victoria newspaper, Le Courier de la Nouvelle Caledonie, published by Paul de Garro, and edited by a W. Thornton. De Garro was said to be a French emigre count from San Francisco who had fled from Paris in 1851. Many of the Fraser River miners and prospectors and some of the new residents of Victoria at this time were also French emigres from California, so there were some potential readers. Le Courier was a tri-weekly, and only nine issues are known to have been printed. There was also a weekly, Edition Hebdomodaire Pour Les Mines les Etats Unis et l'Europe issued on September 18 and October 9, 1858. But there were too few French-speakers to support the papers, so they succumbed after a few issues.

The British Colonist

Dec. 11, 1858 to Aug. 31, 1980 (The Daily Colonist)There were, however, two important legacies. One was Alfred Waddington's The Fraser Mines Vindicated, or, the History of Four Months, the first non-government book produced on Vancouver Island, published by de Garro. The other was the ancient hand press on which Le Courier had been printed. It was this press which was available when Amor de Cosmos came to Victoria to found the British Colonist, and on it, he printed his first issue.

None of these newspapers caused a ripple on the calm editorial

surface of the Gazette; their existence was ignored. The appearance of

the Colonist, in retrospect a political and journalistic landmark, was

apparently not considered newsworthy by the men from San Francisco

since no mention of De Cosmos or his new weekly was made in the

Gazette throughout the whole of December, 1858. In contrast to the

bland tone of the Gazette, the vehemence of the reform-bent Colonist

must have created considerable stir in the community. Yet, despite the

severity of some of the De Cosmos attacks on Douglas and his

government, the Gazette would not reply in kind until its American

pride had been bruised, neither attempting to defend the governor

against the Colonist broadsides, nor joining in criticizing him.

Nothing in this period illustrates the editorial differences between

the two papers better than their respective positions on a

proclamation by Douglas in the spring of 1859 requiring both to post

bonds to secure payment of fines or civil damages in case of

conviction for libel. The bonds required were 400 pounds for each

proprietor of a newspaper, plus two sureties of 400 pounds each.

As historians have pointed out, the proclamation was an obvious

attempt by Douglas to muzzle de Cosmos. But the regulations also

worked against the Gazette. Times were no longer as prosperous as

they had been in the summer of 1858; Victoria's population was on

the wane, and many American merchants were beginning to return to

California. With them went their advertising. The Gazette had already

cut back from daily publication to tri-weekly, it was faced with

populist competition from the Colonist, and 1,200 pounds was a great

deal of money for a small newspaper to lay out, even as a bond. The

proclamation was disagreeable to the Gazette owners, but they

complied with it promptly, commenting mildly that "we regret

that it was not included among those English acts which, in the

discretion of the Governor, are inapplicable to one of these

colonies."

De Cosmos, on the other hand, turned the proclamation to his

advantage, declaring that it "infringed the constitutional

rights" of the colonists. The week before, when the scheduled

issue of the Colonist failed to appear, a public meeting had been

called and 800 pounds quickly pledged by some of Victoria's citizens

to pay the sureties required for Victoria's "independent

press." In one blow, De Cosmos succeeded in polarizing two

kinds of public opinion: opposition to Douglas and anti-American

feelings against the Gazette.

The impression has been given in historical accounts of the

episode that the missing April 2 issue of the Colonist was never made

up because De Cosmos could not afford the bonds. In fact, copies of

the Colonist for that day were printed as usual, but apparently never

distributed and De Cosmos later wrote the following explanation: he

had learned accidentally of the proclamation on April 1 and noting

that a 50-pound fine per issue was the penalty for non-compliance,

hastened to find a government official with whom he could file the

necessary declarations, and so publish the following day. But the

proper officials were inexplicably not to be found, and so the April 2

issues languished in the Colonist office. Nowhere in print does De

Cosmos hint that he could not afford the bonds; indeed, the opposite

is implied.

The issue that was withheld contained on the front page a

particularly venomous attack, even for the Colonist, on Douglas and

his government. The article, signed only by "B.Wm." urged

the colonists to demand the removal of Douglas by the British

authorities; they must get rid of the "present government, with

its lick-spittle characteristics, its crawling and evil proclivities, its

thousand and one faces, and all the corruption which it has

engendered; they must curb its profligate extravagance.....they must

show it to the world in all the hideousness of sin, that honesty may

blush and bow the head....." A shorter, unsigned article on the

same page also called for the removal of Douglas.

Once the bonds had been posted for the Colonist, there was

nothing to prevent De Cosmos from reprinting the articles and giving

them circulation, except the fear of a libel action. But he never did,

and it is likely Douglas had prior knowledge of the projected April 2

attacks. In any case, the relationship between the proclamation and

the withheld Colonist could hardly have been one of simple

coincidence.

The Gazette emerged from the episode looking even more like a

disinterested interloper, but as spring wore into summer, the San Juan

Island controversy caused the paper to bare at last its American soul.

Soldiers from the U.S. had been landed on the island, and the Gazette

said in a lead article entitled "A Teapot Tempest" that the

move was only made to protect American settlers already there from

Indian attack, and there was no violation of "alleged"

British rights. The island obviously belonged to the United States,

"such clearly being the fair interpretation of the treaty [of

1846]," so there was no danger of Anglo-American relations

being impaired unless action was taken from the British side that

would aggravate the situation, a reference to Douglas" desire to

match force with force.

The newspaper's tone was calm but assured. It continued to refer

to the "alleged" rights of Britain, and sent its reporter

"Curioso" to the island to view the situation at first hand.

He wrote back that increasing numbers of American settlers were

arriving to take up land under United States pre-emption laws and

that any attempt to land British troops would be regarded as invasion.

The Gazette commented that Douglas had no authority to land troops

in any case; that was a decision for the home government in London,

and settlement of the matter should be left to the British and

American governments without interference form Victoria.

Then the Gazette offered the ultimate insult. The island it said,

would be wasted on Britain which would make no effort to settle and

develop the disputed territory.. The Americans, on the other hand,

with their heavy western population, would put the island to good use.

To Douglas and those who shared his dread of American expansion,

the Gazette's stance must have acted like a red flag waved in front of a

bull.

New Westminster Times and Vancouver Island Guardian

Published in Victoria: Sept. 17, 1859 - Mar. 10, 1860; Feb. 13, 1861 - Feb. 27, 1861 Enterprises were almost immediately set in motion which would

soon pinch the Gazette out of existence. The first development was

the creation by Douglas of an official government gazette, owned by

Capt. Edward Hammond King and printed by Leonard McClure.

The

second was the founding of another newspaper, the weekly New

Westminster Times and Vancouver Island Guardian. It was owned by

King and Coots M. Chambers, printed in Victoria by McClure and

copies sent to New Westminster on the mainland by steamer.

The

second was the founding of another newspaper, the weekly New

Westminster Times and Vancouver Island Guardian. It was owned by

King and Coots M. Chambers, printed in Victoria by McClure and

copies sent to New Westminster on the mainland by steamer.

The government gazette was a double-edged weapon. Official

notices published in purchased space in the American Gazette and the

Colonist had represented substantial income for the two newspapers.

The official government publication made this practice unnecessary, so

Douglas delivered significant financial blows to both American and

reform organs at the same time.

The New Westminster Times was launched with an announcement

in the first issue of the government gazette, and unlike the Colonist,

drew immediate fire from the American Gazette, which saw in the

newcomer an opponent to be feared more than the Colonist. Ample

grounds for this fear were provided by the first issue of the Times and

reinforced by subsequent issues because the new journal reflected

many of the views of Douglas.

The Times aimed to be an "English-toned newspaper,"

promoting the interests of the mainland colony of British Columbia. It

would not be a radical "erroneously termed liberal," and

the claim was made the the paper's founding had been prompted by

the desires of that "English portion of inhabitants" living

in British Columbia. In appearance, too, the Times was quite different

from the tabloid-like Gazette and Colonist. A spacious five-column

broadsheet, it achieved a dignified typographical display and devoted

considerable space to poetry and purely literary material.

Appropriately, its subscription and advertising rates were quoted in

pounds, shillings and pence, instead of dollars and cents as in the

other two newspapers.

Was the Times in fact, a government-supported newspaper? The

evidence is strong that it was. There were, of course, contemporary

charges that the Times was nothing but a mouthpiece for Douglas;

charges which the newspaper vigourously denied. Yet, here were King

and McClure, both deeply involved in the government gazette,

simultaneously publishing the Times in the same office. Here was the

appeal to the British element of the population that could have come

from Douglas himself. In the months following its creation, the Times

bitterly attacked the mainland colony's lieutenant-governor, Col.

Richard Clement Moody, and demanded his removal; supported the

idea of a colonial mint, tilted spiritedly with De Cosmos and his

political allies; and while advocating somewhat more liberal political

institutions for the mainland colony of British Columbia, praised

Douglas for doing a good job under difficult circumstances. Nor did

the Times have much visible means of support. Its advertising was

skimpy, compared to the Gazette and Colonist of the day.

For the first time, the Times trained its main editorial guns on the

Gazette for its San Juan position. The Times pictured Douglas as a

man accused of provoking a disturbance because he resists someone

breaking into his house. There was no doubt, the paper said, that the

Island belonged to Britain and it was being clandestinely seized by an

armed force of Americans. By the second issue, the Times was raising

alarums of possible American attacks on Vancouver Island and

suggesting that a militia be immediately formed in Victoria. Soon, the

Gazette was being ridiculed by the Times as a paper ignorant of

English history and the English language, and it was only a short step

from that to printing a letter from an anonymous correspondent

branding all American journalism as "below

mediocrity."

By now, the Gazette had been stung out of its equanimity and

was resorting to some name-calling of its own. Emotionally, it

defended the American political system. In an effort to compete with

the Times in British Columbia where many of the Gazette's gold-miner

readers were, the paper launched a running attack throughout

October and most of November on government policies on the

Mainland. It railed against "turkey-strutting by government

officials and in some cases, extortion" which were causing

miners to return south of the border. The Hudson's Bay Company

came under attack for its land policies and the Vancouver Island House

of Assembly for its ineptness.

Victoria Gazette #2

Dec. 5, 1859 - Sept. 29, 1860 But the squeeze on the Gazette was too powerful. On November

26, 1859, the San Franciscans bitterly acknowledged that controls

imposed by Douglas on American miners had ruined their market

while the Colonist and the Times between them had overcrowded the

field. Complaining that three newspapers "have been thrust

upon a community that can hardly afford a legitimate support for

one," the Gazette announced it was not interested in cut-throat

competition for survival, and so the owners were withdrawing to more

profitable fields.

Curioso (John Damon) remained behind, and to him, the Gazette

proprietors sold the goodwill and name of their paper. He never had

an opportunity to exploit either. Almost before the body of the old

Gazette was cold, a new one was born; a brother of the Times,

produced on the same size paper with the same type in the same

printing office by the same people: King and McClure. And the instant

tri-weekly adopted the same pro-Douglas and anti-De Cosmos stance

as the Times, too. Damon protested in vain that the paper's name had

been stolen from him. Recourse to the courts resulted in a temporary

injunction against the Victoria Gazette and for a few issues the paper

appeared without any name on its masthead as the case for a

continuation of the injunction was argued. Not surprisingly, Judge

David Cameron, brother-in-law to Douglas, decided Damon had no

clear title to the name. It was obvious that any attempt to re-establish

even the hint of American ownership was to be stamped out.

De Cosmos was now the only independent newspaper voice left in

the colony. King and McClure were still printing the government

gazette as well as the Times and Victoria Gazette which were in reality

different editions of the same newspaper. Type for notices, news

items, advertisements and even lead articles was often simply used

from one newspaper to the other without any change in appearance or

content. Advertisers did not have to pay twice to appear in both

journals; the rate for double exposure was only one-half more than for

single newspaper publication.

McClure's connection with the Victoria Gazette involved him in a

journalistic feud with David Williams Higgins, who had just joined the

Colonist, over the ejection of a man from a meeting called to discuss

a mule tax. Higgins claimed the man was a Victoria Gazette reporter.

The battle of words raged over several issues of both papers, with

McClure referring to Higgins as "Sniggens or Muggins"

and getting labelled by Higgins in turn as "Booby

McClure." The two were later to conduct a business transaction

which deeply affected both their lives, but did not change their dislike

for each other.

Meanwhile, even as McClure sniped at Higgins, he was arranging to buy the Times from King and move it to New Westminster, bringing out the first British Columbia issue March 17, 1860 on the mainland colony's first printing press. Alive to the historic nature of the occasion, McClure later wrote "...I toiled up the steep ascent, over logs and stumps, through brush and tumbled weeds, hauling with the aid of the unwilling savage, the first printing press in British Columbia." Joining the Times staff shortly after was John Robson.

Back on Vancouver Island, the Victoria Gazette was being

purchased from King and McClure by George Nias, who, since he had

at the same time purchased the government gazette, did not change

the newspaper's generally docile tone. But wherever McClure went at

this time, it seemed, government patronage was sure to follow, and

less than six months after the Times had been established in New

Westminster, it was announced that the government gazette was being

discontinued as a separate publication, and would instead be

published as part of the Times. It was the death blow for Nias'

publishing business. Complaining of the the "base deception of

men in high places," Nias closed the Victoria Gazette, leaving

the Victoria field to the Colonist, which found itself in a monopoly for

the first time.

Now McClure was beginning his rise to prominence in earnest. At

first, he continued to side the with colonial government. Using the

Times to boost both his own position and that of Douglas in Mainland

British Columbia, he was elected president of New Westminster's first

municipal council, then headed a group seeking to be named as city

representatives to a British Columbia convention to press Douglas for

major reforms in the governing of the colony. Opposition developed to

McClure's "Government Ticket" which wanted merely to

assist and advise Douglas, and a rival "Reform Ticket" was

organized which wanted a resident governor and representative

government institutions. McClure's ticket was defeated and his

comment on the outcome was that election proceedings had been in

"the hands of a mob." But behind those words, a new

McClure was in the making.

Within a month, McClure had agreed to move the Times back to

Victoria and sell his Mainland newspaper office to a group of citizens

who planned to make Robson the editor of a new reform paper, The

British Columbian. McClure threatened to return to New Westminster

if The British Columbian was not to his liking, and then bade

adieu.

The Daily Press

Mar. 9, 1861 - Oct. 16, 1862 Once he had returned to Victoria, McClure published only two

more issues of the Times, then had a remarkable change of political

heart. He transformed the Times into a completely different

newspaper, and changed the name to The Press. It soon rivalled and

then surpassed the Colonist as a biting and persistent critic of

Douglas.

What was behind McClure's abrupt conversion from government

lackey to reformer? The simple answer appears to be: ambition.

Opportunist by nature, he began by attaching himself to the Douglas

establishment because that seemed the surest way to rise. But in New

Westminster, where rumblings against the despotic policies of Douglas

were much louder than in Victoria,

McClure's defeat as a convention

candidate and the many other signs of unrest must have convinced

him that the Douglas star was waning quickly. It was time for McClure

to play a new role, and the sale of the Times could well have provided

McClure with the money to found another newspaper, this time to

assail his former benefactor.

McClure's defeat as a convention

candidate and the many other signs of unrest must have convinced

him that the Douglas star was waning quickly. It was time for McClure

to play a new role, and the sale of the Times could well have provided

McClure with the money to found another newspaper, this time to

assail his former benefactor.

McClure was joined in his new publishing venture by partners John Jessop and two compositors, but Jessop did not stay with The Press more than a few months.

One of the few published references that exist about The Press

describes it as a money-losing operation, going to press

"sometimes on colored wrapping paper on account of lack of

funds to purchase white." While this may have been true in the

early stages, the evidence provided by the paper itself points towards

a successful business enterprise.

Started as a tri-weekly, The Press became The Daily Press within

a month, publishing at first in the morning in direct competition with

the Colonist, then switching to afternoon publication. Advertising

initially took up about 60 per cent of the paper's space,

but by the end

of the first year, occupied nearly all the space, so that only about four

columns out of twenty were being devoted to news and opinion. On

two occasions, the Press was indeed printed on coloured paper that

could have been wrapping material; once it came out for several issues

on dark brown paper and later, appeared on bright yellow paper. The

reason given on each occasion was that the steamer carrying the

normal supply of paper from San Francisco had been delayed. Another

Victoria newspaper later provided the same explanation when it had to

be printed on sheets different from the normal size, so the Press

explanation is a reasonable one.

but by the end

of the first year, occupied nearly all the space, so that only about four

columns out of twenty were being devoted to news and opinion. On

two occasions, the Press was indeed printed on coloured paper that

could have been wrapping material; once it came out for several issues

on dark brown paper and later, appeared on bright yellow paper. The

reason given on each occasion was that the steamer carrying the

normal supply of paper from San Francisco had been delayed. Another

Victoria newspaper later provided the same explanation when it had to

be printed on sheets different from the normal size, so the Press

explanation is a reasonable one.

The Press provided a synopsis in its first number of the issues to

which it would address itself over the next twenty months: the

incompetence and self-seeking nature of the Colonist proprietor; the

greediness of land speculators and "that concoction of selfish

ignorance and legislative stupidity -- our excrecable land

system;" the deception and opposition to reform of an

"imbecile government."

Five days later, the Press was attacking Douglas by name for

failing to introduce representative institutions to Mainland British

Columbia. "We have blundering and ignorance a thousand times

worse than ever attended an incipient colonial Parliament ... We are

sick of the obstinacy of Governor Douglas on this question. We are

disgusted with his supercilious and impractical advisers."

McClure continued to hound Douglas issue after issue, finally losing

all patience and laying the responsibility for lack of reform directly at

Douglas' feet. "No man knows better than Douglas," the

Press thundered, "that his House of Assembly is used as an

ignoble breakwater to protect His Serene Highness from the waves of

popular indignation."

There can be no doubt that the Press now eclipsed the Colonist

as a critic of Douglas. Alluding to De Cosmos as "the miserable

government hack," McClure claimed that the Colonist had lost

its crusading spirit of 1859 and had "succumbed to the Chinese

obsequiousness of 1861." To a considerable extent, the charge

was accurate. De Cosmos was writing with his usual vituperative

energy, but his aim was diffuse, and Douglas was no longer a prime

target. Advertising, meanwhile, increased in the Press and McClure

won a printing contract over De Cosmos from the newly-created

Victoria city council.

But even as he seemed to be reaching a pinnacle in journalism,

McClure was preparing to abandon the field and lay the foundations

for a political career. In New Westminster, Malcolm Cameron, a

Canadian politician visiting the western colony, had been chosen to

travel to London and present the many grievances of the British

Columbia colonists against Douglas to the Duke of Newcastle, Secretary of State for

the colonies. McClure proposed that Cameron should also become a

representative for Vancouver Island because, despite McClure's best

efforts, the Douglas regime seemed as strongly entrenched in late

1862 as it had been three years earlier. The problem, said McClure,

lay in disunity among reform elements in Victoria. He felt they must

submerge their differences and send a petition with Cameron to

Newcastle.

Two days later, answering a letter to the Press from

"Monitor" who said that the remedy for the colony's ills

lay in the available electoral processes, McClure pointed out that

under the existing distribution of seats, government and rural

"pocket boroughs" could outvote Victoria and stall reform

indefinitely. Then McClure planted his seed. If there were those who

objected to Victoria's joining with New Westminster in naming

Cameron as a representative to the Imperial government "on the

ground that a stranger, no matter how talented or how experienced, is

not suited for the task, let them bring forward a townsman." By

"townsman," McClure meant himself. The seed sprouted.

Within two weeks, McClure sold the Press and within a month, was on

his way to England with Cameron to see Newcastle.

The Victoria Daily Chronicle

Oct. 28, 1862 - June 23, 1866 The sale of the Press brought onto the newspaper stage two

experienced journalists who had been waiting in the wings, David W.

Higgins and

James Eliphant McMillan. They were to bring to the

colony a kind of journalism not yet seen. Both were reform-minded,

but both found distasteful the flamboyant, personal styles of De

Cosmos in Victoria and Robson in New Westminster.

In Higgins' case, this aversion led to a break with De Cosmos, for

whom Higgins had been working just before McClure put the Press

up for sale.

De Cosmos planned to persuade a black saloon-keeper,

Jacob Francis, to stand in the next election for House of Assembly

members, with Colonist backing. The ploy was to serve as revenge on

Douglas, who had caused citizenship to be given to about 50 blacks

for the last election, in which De Cosmos had been defeated. Higgins

found the De Cosmos plot repugnant because Francis was, in his

opinion not fit to run for public office. Higgins resigned, and would

not return to the Colonist even when De Cosmos agreed to abandon

his scheme and give Higgins a share in the newspaper. Instead,

Higgins went to McClure and made a cash offer for the Press, which

he knew was for sale. McClure accepted, and McMillan took a half-

interest in the venture.

De Cosmos planned to persuade a black saloon-keeper,

Jacob Francis, to stand in the next election for House of Assembly

members, with Colonist backing. The ploy was to serve as revenge on

Douglas, who had caused citizenship to be given to about 50 blacks

for the last election, in which De Cosmos had been defeated. Higgins

found the De Cosmos plot repugnant because Francis was, in his

opinion not fit to run for public office. Higgins resigned, and would

not return to the Colonist even when De Cosmos agreed to abandon

his scheme and give Higgins a share in the newspaper. Instead,

Higgins went to McClure and made a cash offer for the Press, which

he knew was for sale. McClure accepted, and McMillan took a half-

interest in the venture.

McMillan had been a partner in the publication of the British

Columbian and had just parted company with Robson, undoubtedly

because of a disagreement over Robson's vigourous anti-Douglas

writings. In a letter printed in the Colonist but addressed to the editor

of the British Columbian, McMillan accused Robson of being unfair

and unreasonable in his attitude towards Douglas, taking the view that

while there were many wrongs that needed correcting, Robson's fiery

editorials were not the way to obtain reforms.

McMillan also had some praise for Douglas, and his respect for

the governor's personal ability -- if not all his politics -- was shared by

Higgins. The two men changed the name of the Press to the Victoria

Daily Chronicle, switched from afternoon to morning publication to

compete directly with the Colonist and after the first two days of

publication, claimed that canvassing had produced more than 420 new

subscriptions, certainly an auspicious start that augured ill for the

Colonist.

The traditional statement of position in the first issue of the

Chronicle said that the paper would advocate liberal reform measures,

regardless of who supported them, but would not, "like some of

our contemporaries, indulge in factious opposition to the Government,

or make the Executive the object of personal vituperation and abuse.

This, we regret to say, has been too much the case, both in this and

the neighbouring colony, " weakening the cause of reform and

retarding progress. This was a new style of colonial journalism; a more

sophisticated kind that, for the most part, would attack principles

instead of people and aim at reaching a broad segment of reform

opinion that contained differences of outlook about individuals. For

the first time, Victorians could read a newspaper with an outspoken

tone that was balanced.

The Chronicle advocated a better application of British laws and

institutions to the colonies; a more representative assembly made up

of men who were not interested only in personal gain, as the present

members were said to be; the development of an agricultural economy

to provide the kind of stability a gold-rush economy could not; a

proper education program, which had been neglected. At the same

time, the paper maintained a strong attack on the Colonist, claiming

that De Cosmos' only principle was self-interest and that his paper had

been obtaining "thousands of dollars worth of printing"

from the government without tender.

But while the two newspapers were often at odds, they did agree

on their disapproval of McClure, who was circulating a petition of

grievances that was to be taken with Cameron to London.

"Beyond the gratification of a boyish ambition," wrote De

Cosmos, "McClure doesn't have a dollar's fixed interest in either

colony." Nevertheless, at a town meeting the next evening,

McClure won the nomination as Cameron's partner, beating out

Victoria businessman Alfred Waddington who wanted 2,000 pounds

of expenses. McClure told the meeting he was going to England

anyway, and would pay his own way, a happy circumstance that

probably resulted from his sale of the Press. The Chronicle commented

sourly that the gathering had been "a meeting of

monstrosities" and "not one fiftieth portion of inhabitants

are in favor of Mr. McClure as a delegate," but a week later,

McClure set sail for England with Cameron, bearing a petition from

Victoria to Newcastle that had more than 1,000 names on it.

Early in April, 1863, the Chronicle put out an extra edition to print a letter from McClure in Britain to Victoria council member John Copland in which McClure announced "we have succeeded in ousting Governor Douglas and I think Carey and rest will have to follow suit."

The next day, the Colonist printed the same letter and the

Chronicle repeated it, adding its own comments that were critical of

McClure for writing that Douglas was to be dismissed. Obviously, the

paper said, Douglas was simply to be relieved as expected and it was

an insult to his position to suggest that the Home government was in

any way displeased with the governor. The Colonist refrained from any

full editorial comment, noting mildly in a small paragraph among the

local news items that, judging from McClure's letter, it looks like

"rather a clean sweep." A few days later, a correspondent

signing himself "Nemo" wrote in the Chronicle that the

McClure letter was a fabrication, but the paper itself dismissed this

notion, saying that Copland and others were prepared to swear the

letter was authentic.

The Daily Evening Express

Apr. 27, 1863 - Feb. 2, 1865The "Nemo" letter seemed to be a signal for a renewed

burst of activity by the pro-Douglas forces. Two weeks after its

publication, the Daily Evening Express was born, an afternoon journal jointly owned by Charles Allen and George Wallace. It was

kept out of direct competition with the two established morning

newspapers, and heaped praise on Douglas and his

accomplishments.

The Express was answering the need for "a

truly British paper," which would be opposed to the introduction

of "foreign elements" into the assembly and the

"democratic" innovation of universal suffrage.

The Express was answering the need for "a

truly British paper," which would be opposed to the introduction

of "foreign elements" into the assembly and the

"democratic" innovation of universal suffrage.

In many ways, the Express was another New Westminster Times and told its readers that while it was true that Douglas was about to retire as governor of Vancouver Island, he was probably going to be appointed governor of mainland British Columbia. His leaving Victoria would be regretted because his administration "has been marked with the most paternal considerations" for the island's welfare and progress.

In September, 1863, a petition was circulated in Victoria asking

the home government to retain Douglas in office. The Chronicle

viewed the petition as an attempt to place the colony under a life

governorship; the Colonist denounced it, and De Cosmos stated that if

Douglas retired, he would never again criticize the governor in print.

But the Express, while doubting the petition would be successful, saw

it as a tribute to the "affections [sic] and esteems"

Douglas had earned.

The only other issue to which the Express addressed itself with

any liveliness was the political ambition of De Cosmos, who was

preparing to run again for a seat in the assembly. The paper was as

scornful of De Cosmos as it was admiring of Douglas. Other colonial

topics were virtually ignored; instead, the Express subjected its

readers to great numbers of long, dull commentaries on events in such

places as Poland.

The paper's shower of accolades for the retiring Douglas marked the closing of a newspaper era. Before the end of the year, De Cosmos had sold an interest in the Colonist to two of his employees and turned his full attention to politics. The Chronicle rose to a pre- eminent position, taking over the Colonist office and name with Higgins at the helm for another twenty years. McMillan was soon to begin his own newspaper and become attached for a while to the movement for annexation to the United States. So, eventually, did McClure, who returned quietly from London in 1864, and became editor of the Colonist and an assembly member for Victoria before starting his own newspaper. The Express continued until 1865, but it turned to new causes once Douglas was out of office.

* * *

As governor, Douglas had been like a sun around which the newspapers circled, and if he had appeared officially indifferent to their barbs and bravos alike, the depth of his reaction to the storm of ideas they brewed can be gauged in the columns of the early Express, the second Victoria Gazette, and the New Westminster Times. As for the newspaper editors of the period, two went on in political life to become premiers of British Columbia, another became a post- Confederation speaker of the legislature; a fourth became mayor of Victoria.

And out of the brief torrent of competing opinions in the pages of so many different newspapers, political reform rushed headlong once Douglas was no longer in charge.

Cast of characters

James Douglas

Vengeance seeking friends of a murderer who had suffered frontier justice from Hudson's Bay Company agents at Fort St. James, captured a young company clerk in1828 and. threatened to kill him. But they accepted a gift of supplies instead and the clerk was freed, Thus James Douglas was spared to become the first governor of the mainland colony of British Columbia.Born in British Guiana in 1803, this son of a Glasgow merchant entered the fur trade at 15 and later married a factor's daughter of Cree descent. While serving as an accountant at Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River, he rose to the committee of management and was sent to Vancouver Island to establish a fort in 1843. This was the founding of Victoria and ultimately the colony of Vancouver Island.

He succeeded Richard Blanshard as the island colony governor in 1851 and in 1858 became the first governor of the mainland colony, holding both offices until 1864 when it was felt each colony should have its own authority. Retired and knighted, when the colonies were joined in 1866, he lived only another 11 years and was buried at Victoria. (Back to text)

James W. Towne, Henry C. Williston and Columbus Bartlett

James W. Towne founded the San Francisco Christian Recorder in August, 1854 and the San Francisco Weekly Intelligencer in May, 1856 with Abel Whitton, who was a silent partner with Towne in the Gazette until Sept. 1, 1858 when the Gazette announced that Whitton had bought out Towne's interest in the company owning the Gazette. Towne was also part owner of the San Francisco Times and the California Culturist monthly magazine, both started in 1858. Williston had been editor and co-publisher of the San Francisco Wide West and editor of the Weekly Sunday News before coming to Victoria. Bartlett had joined with F. W. Pinkham to publish the San Francisco Daily News from 1853 to 1856 and was one of the proprietors of the Daily True Californian in 1856. Two brothers, Julian and Washington Bartlett, were also active in California newspapers, with Washington eventually becoming mayor of San Francisco and a governor of California. (Back to text)John Damon

John Fox Damon was born in Waltham, Mass., in 1827 and became a printer's assistant at the age of 10 in Lynn, Mass. In 1849, he emigrated to the California gold fields and spent 17 months in the mines, later going to San Francisco where he worked for the Alta California as a printer. Surviving an attack of cholera, he moved to San Jose and became editor of the Visitor for awhile, then went to San Diego. There he became a correspondent for San Francisco and Massachusetts newspapers, adopting the pen name "Curioso" for the first time. He arrived in Victoria some time in 1859, working as both a reporter and compositor for the Gazette. In the spring of 1859, he was sent by the Gazette to the British Columbia gold fields on the mainland to report on conditions there. A photocopy of a notebook of his is in the manuscript collection of the B.C. Archives listed as a diary. It is actually the reporter's notebook from which Damon wrote his gold-field articles for the Gazette.(Back to text)Frederick Marriott

Frederick Marriott was born in Enfield, England July 16, 1805. He was sent at an early age to work with the East India Co. in India, and upon his return to England, became a journalist and started what later become the Illustrated London News. He immigrated to California in 1849, engaged in real estate in the gold mining areas, and started the San Francisco News Letter in 1856 before coming to Victoria. In late 1858, he left Victoria rather hurriedly under a cloud concerning a missing $8,000, and returned to California. His San Francisco News Letter flourished until 1928. Marriott was also well-known in the United States as an aircraft pioneer. In 1869, a dirigible-type flying machine designed and built under his direction was successfully flown at field near the present San Francisco airport. It was called the Avitor. During later tests, it caught fire and was destroyed, discouraging further support for the project. Marriott is said to have coined the term "aeroplane." In 1878, two years after the invention of the telephone, Marriott bought and installed two of the new instruments. One was in his News Letter offices, the other in his home. They were the first telephones in San Francisco. Marriott died Dec. 16, 1884.(Back to text)Paul de Garro

Count Paul Joachim d'Urtubie de Garro was an aristocratic fugitive from the French revolution of 1848. His wife was killed during fighting in Paris, and because de Garro was opposed to Napoleon III, he was exiled to California in 1851. He came to Victoria in 1856 and at one time, worked as a waiter in a restaurant. In 1861, he decided to move to the new Cariboo gold fields on the mainland and went aboard the steamer Cariboo Flyer to get there. Before the ship could leave Victoria, there was an explosion aboard, and De Garro and five others were killed.(Back to text)Amor de Cosmos

Born William Alexander Smith in Windsor, Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1825, he was well-educated, and when he was 28, was attracted to the goldfields of California, where he became a photographer. It was while in California that he petitioned the legislature there to change his name officially. In his petition he said: "I desire not to adopt the name Amor de Cosmos because it smacks of a foreign title, but because it is an unusual name, and its meaning tells what I love mostly, viz: love of order, beauty, the world, the universe." He arrived in Victoria from California in June of 1858. De Cosmos sold his stake in the Colonist in 1863, but in 1870, started another Victoria newspaper, the Standard. His political career began in 1863 when he was elected to the Vancouver Island colonial assembly. After Canadian Confederation in 1867, de Cosmos was elected to the British Columbia legislature, and was at the same time, elected as a Member of Parliament to Ottawa. He became the second premier of B.C. in 1872 and retained his MP's seat as well. De Cosmos resigned as B.C. premier in 1874 and died in 1897.(Back to text)Edward Hammond King

King was born in England in 1832 and joined the British Army in 1851, serving in India and China until his retirement because of ill health in 1858. He came to Vancouver Island by sailing ship in 1859, and was accidentally killed in March, 1861 while investigating a wreck.(Back to text)Leonard McClure

McClure was born in Belfast, Ireland, about 1836 and brought up in the printing trade. Emigrating to Australia at an early age, he became connected with several newspapers, then went to California, where he was engaged on a newspaper in the mining districts. He is first heard of in Victoria in the early fall of 1859 as a partner of King. McClure left Victoria in 1866 to become editor-in-chief of the San Francisco Times. He died there in 1867(Back to text)David Williams Higgins

Higgins later said he joined The Colonist as "editor, reporter and all-round businessman, rolled into one for the sake of economy". Born in Halifax, N.S. in 1834, Higgins was taken by his parents to Illinois and then to Brooklyn, N.Y., when he was two. Educated in the printing trade, he travelled to San Francisco in 1852 and was one of several founders of the Morning Call there. He followed the gold miners north to the Fraser River fields before coming to the Colonist. He became one of B.C.'s most illustrious journalists and authors, closing out his newspaper career as editor of the Vancouver World in 1906-07. Higgins was also Speaker of the B.C. House of Assembly after Confederation from 1890 to 1900. He died in 1917.(Back to text)John Robson

Robson was born in Perth, Upper Canada in 1824, moved to mainland British Columbia in 1859, and became editor of the reform newspaper The British Columbian in 1861. He began his political career in 1871 as the member for Nanaimo in the legislature, and became premier of B.C. in 1889. He died in office three years later.(Back to text)George Nias

A native of Yorkshire and a printer by trade, Nias came to Victoria in 1858 or earlier from San Francisco. He later worked for the Colonist and in 1867, after his request to be appointed government printer was turned down, emigrated to Melbourne, Australia with his family.(Back to text)John Jessop

Jessop was a school teacher from Ontario who had come overland to British Columbia about 1860 and had worked with McClure on the Times in New Westminster. In the summer of 1861, he set up a non-sectarian school in Victoria, and after British Columbia joined Confederation, he became superintendent of schools for the province.(Back to text)James Eliphant McMillan

Born in Niagara, Ont., July 25, 1825, McMillan learned to be a printer as an apprentice on three early Toronto newspapers, then was involved as either editor or proprietor (sometimes both) on six small papers in Dumfries, Oshawa and Bowmanville. He came to Victoria in May, 1859 and was hired by De Cosmos for the Colonist. In April, 1861, he moved to the New Westminster Columbian. He later moved back to Victoria, and after selling his share in the Chronicle, began his own newspaper, the Morning News. He later became editor of The Standard, and was also elected mayor of Victoria in 1872 and 1873. He retired from journalism in 1875, and the next year was appointed immigration agent for Victoria. In 1884, he became sheriff for the district of Victoria. McMillan died in Victoria on August 13, 1907.(Back to text)Charles Allen and George Wallace

Allen was an Englishman who is first heard of in Victoria as a reporter for the Colonist in 1862. Wallace was born in Boston, Mass. in 1833, came to Vancouver Island overland and joined the Colonist at about the same time as Allen. He later founded the Cariboo Sentinel in Barkerville in June, 1865, selling out to Allen a year later and starting the Tribune at Yale. Both men closed their newspaper careers outside of British Columbia; Wallace at the Montreal Mail, and Allen with the Manitoba Free Press.(Back to text)

PHOTO CREDITS: The newspaper mastheads, front pages and most of the pictures are from the British Columbia Archives. The picture of Frederick Marriott is from a web site about him: Frederick Marriott and the Avitor. The picture of Leonard McClure is courtesy of the City of New Westminster, B.C.

Comments? Click here to E-mail

This page was started in February, 1999. It was last revised on Jan. 29, 2010

© Hugh Doherty 2013